Let's get reading

The reading skill is built on a foundation of language skills children start acquiring from the earliest days. When talking about developing the reading skill from the parents` perspective, I don't think in terms of explicit teaching. Most parents already help their children acquire this skill without doing it intentionally.

Table of Contents

But, before we answer some whats and how, here are a few interesting facts about reading:

- Being engaged in more reading and hobby activities is associated with a lower subsequent risk of incident dementia. Reading helps your brain stay active and engaged, which prevents it from losing power. We could say that reading is like a brain gym. So, those who read more are less likely to suffer from dementia[i]

- Reading makes your vocabulary grow and expand. Written text allows many more word-learning activities than talking or watching television[ii

- Parents who read one picture book with their children every day provide their children with exposure to an estimated 78,000 words a year. Now, if we do some maths, over the five years before pre-school entry, we can estimate that children from literacy-rich homes hear 1.4 million more words during storybook reading than children who are never read to[iii]

- Reading strengthens focus and concentration.

- If you want to read the longest English sentence, look for 'The Rotters' Club', a book written by a novelist Jonathan Coe. There you can find a sentence consisting of 13,955 words. It spans a length of 33 pages.

Reading stages

Children start building their reading skill as babies, way before they can decode or recognise and sound out words they see. Becoming a fluent reader is the last milestone in the development of the reading skill.

Important: children develop at different paces and spend varying amounts of time at each stage.

| Age | Children usually[iv |

| 0 -1 | Direct their attention to a person Understand 50+ words Reach for books Turn pages with some help Respond to stories and pictures by vocalising and patting the pictures |

| 1-3 | Name familiar pictures Use pointing Pretend to read Finish sentences in books they know well Know the names of the books and have a favourite one Turn pages |

| 3-6 (emergent reader) | Know some letters (associated with their name, friends, family) Understand that books tell a story Recognise and produce words that rhyme Retell the main idea Begin to match written words to spoken words Read simple words in isolation |

| 6-7 (early readers) | Use different strategies to work out words: spelling using pictures using context Correct themselves as they try to spell out words Show comprehension through drawing |

| 7-8 (transitional readers) | Start reading silently Recognise punctuation marks Become better at self-correcting |

| 8-14 (fluent readers) | Use reading for all areas of their schoolwork Read longer texts Use various strategies to identify words and their meanings Find the information Analyse and question what they are reading |

Threads of reading

Many parents and kindergarten teachers seem to be in a rush to get children decoding, spelling, and attending to the print. But should this be set as a priority in pre- and during kindergarten time? Why skipping playing with sounds just to get to spelling faster?

Many reading experts agree that each thread of reading is equally important, and not a single one can be missing.

In this chapter, we will focus on:

- Print awareness

- Phonological awareness

- Vocabulary

- Comprehension

Each part describes what a thread is and what parents can do to help develop it.

Print awareness

What's print awareness?

It is understanding that print represents words that have meaning and are related to spoken language.

Children who have print awareness can do things like hold a book correctly and understand that books are read from front to back. They also realise that we read from left to right (or from right to left in Arabic, Aramaic, Azeri, Maldivian, Hebrew, Kurdish, Farsi, Urdu).

What can parents do?

Younger children (0 - 3)

- Mention the parts of a book as you read. "Look at this cover! This book must be about cats!" "The End …that's the last page of the book."

- Have your child help you turn the pages.

- Model that we read from left to right (or right to left) by occasionally running your finger under the text as you read.

With older children (3 – 6) you can ask them to show you:

- The title

- Where you should begin reading

- A letter/ word

- The first/ last word of a sentence

- The first/ last word on a page

Occasionally point out periods and exclamation points.

Help your child create signs for different things in the house, such as "Welcome to my room," "Bathroom," "Lego", "Chair".

Phonological awareness

What's phonological awareness?

It's a big term, but it's really quite basic: it is the ability to hear and identify the various sounds in spoken words. For example, a child with developed phonological awareness can identify /d/ in words: dog, dish, and mad. He/she can recognise and use rhymes, break words into syllables, blend phonemes into syllables and words, identify the beginning and ending sounds in a syllable.

It is a key indicator of how well children master the reading skill, and this is why learning letters` names is not as nearly as important as learning their sounds.

What can parents do?

These games can be played while taking a walk in a park, reading a book, travelling, cooking or doing any other everyday activity. No print outs, tasks or any form of explicit teaching. Just fun and play.

- Guessing

I spy something red starting with /s/.

- Connecting

What starts with /d/ and ends in /ak/?

- Breaking apart

Oh, look, a cowboy. Now take away boy. What word is left?

- Rhymes

Stage 1 – a child hears and gets accustomed to rhymes

Stage 2 – a child can recognise that the words cat and hat rhyme

Stage 3 – a child can think of a word that rhymes with another. I'm thinking of a word that rhymes with …

- Sally Sound Snatcher (Making new words by deleting initial phonemes)

Introduce a puppet Sally that eats sounds. (If you are playing the game in a car or a park, you can pretend to be Sally). Say the word farm, and then arm. Which sound did Sally snatch? /f/. continue with other words ((t)able, (h)at, (l)ate, (p)each, (c)up, (c)at, (m)eat, (s)ink, (m)eat, (s)eat, (j)am). Then switch roles, and the child gets to be sally.

- Change your name (Initial Sound Substitution)

"Change the first sound in your name, in your name, in your name,

Change the first sound in your name, what's your new name?"

This is when Jack and Mike become Mack and Jike.

- Word chains (in Croatian known as "Kaladont")

Each word should begin with the last sound or syllable of the previous word. In the beginning, don't forget that the focus is on sounds, not letters. Sound and letter correspondence is a bit tricky in English. But this is yet another topic. For this game, before the child learns the ABCs, just play with sounds.

For example: egg – glass – snow- open

/eɡ/ - /ɡlɑːs/- /snəʊ/ - /əʊpən/

Vocabulary

What's a vocabulary?

A vocabulary is a set of familiar words within a person's language. It is, alongside with grammar and pronunciation, one of the micro-skills in a language. Some would argue that it is the most crucial micro-skill to develop. I mean, without grammar, you can say something, but without word… not really.

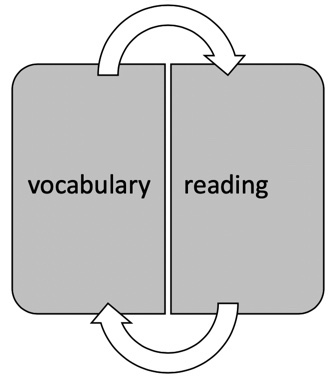

Pupils who come to pre-school/junior infants with a rich and varied vocabulary tend to have a better understanding of the texts they read and, as their reading comprehension increases, their vocabulary knowledge expands accordingly.

What can parents do?

- Talk, read, sing. Talk, read, sing. And repeat.

- Details.

Example: You can say: bring me the book about dinosaurs or bring me the green book about the dinosaurs. The one your grandma and grandpa brought when they were here last month. Ask the same of them. If they ask you to read the book about the Universe, ask them to explain precisely which one.

- Explanation

Use kid-friendly definitions of new words.

Example: we were reading a book in Croatian about a little fairy Kosjenka and a giant called Regoč. The giant was enormous. "Enormous" means that something is really, really big.

After riding for days, Kosjenka and her horse were exhausted. "Exhausted" means feeling so tired that you can hardly move.

- Examples and personalisation

Make connections between what you read and what the child read or experienced before.

Example: As we were reading a story about Kosjenka, I asked some questions: Do you remember when we read the story about Clifford? Now, that was an enormous dog. I would probably feel exhausted after a day like that, helping the firefighters, lifting taxies, running away from a bull, jumping over a fence…

- Using imagery

Pictures and illustrations can be a powerful ally when it comes to developing a child's vocabulary.

Comprehension

What's comprehension?

It is the reason for reading. If readers can read the words but do not understand or connect to what they are reading, they are not really reading.

Good comprehension skills enable children to understand the story, remember it, discuss it, and even retell it in their own words.

What can parents do?

One way is asking questions before, during and after reading. Here, you can see some examples of how to ask questions to help your child understand the text better.

You might wonder how to ask questions if a child is not talking yet. There is one strategy parents can employ while reading – modelling. It shows children what comprehension actually looks like during reading.

Let's take the cover page of a well-known book, The Cat in the Hat, as an example.

The cat in the Hmmm. What rhymes with cat? A mouse? No. Cat. Hat. The cat in the hat. (Run your finger under the text as you read). This is the cat. And the hat (pointing at a picture). This is the title of the book. And look, this is the author (pointing), Dr Seuss. He wrote this story. I wonder what the story is about. What do you think? Why? I think it is about a cat and two children. Do you like cats?

With time, children gradually start to read independently, applying the strategies they acquired while listening to the parent reading.

[i] Hughes, T. F., Chang, C. C., Vander Bilt, J., & Ganguli, M. (2010). Engagement in reading and hobbies and risk of incident dementia: the MoVIES project. American journal of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 25(5), 432–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317510368399

[ii Cunningham, A. & Stanovich, K. (2001). What Reading Does for the Mind. Journal of Direct Instruction, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 137–149.

[iii]Logan, J., Justice, L., Yumuş, M., Chaparro-Moreno, & Leydi, J. (2019). When Children Are Not Read to at Home. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics: 2019 - doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000657

iv Adapted from https://bilingualkidspot.com and https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/milestones.html